I tend to be optimistic about technology, and so I’m often asked by friends… Um, why? I haven’t always answered that question as well as I would have liked and so I wanted to try to do so here. To make the case for technology as a driver of human welfare, I’ll start with the macro-historical view. I’ll suggest that the world is improving and that technology appears to be playing a central role. Then I’ll get into why economists expect technology to be a key driver of economic growth, in line with the broader historical picture. Next, I’ll present some more direct, plausibly causal evidence for technology’s benefits. Finally, I’ll discuss the role of institutions, culture, and policy. And I’ll end with a short case study.

The big picture

Human welfare has improved in any number of ways over the past two hundred years, whether measured through life expectancy, GDP per capita, homicide rates, or any number of other variables. (I’m borrowing charts from the excellent site OurWorldInData.) Not everything is improving, of course, and this sort of progress can’t be cause for complacency. But it is real nonetheless.

As the economic historian Robert Gordon writes, “A newborn child in 1820 entered a world that was almost medieval: a dim world lit by candlelight, in which folk remedies treated health problems and in which travel was no faster than that possible by hoof or sail.” But things changed, not so much gradually as all at once. “Some measures of progress are subjective,” Gordon continues, “but lengthened life expectancy and the conquest of infant mortality are solid quantitative indicators of the advances made over the special century [1870-1970] in the realms of medicine and public health. Public waterworks not only revolutionized the daily routine of the housewife but also protected every family against waterborne diseases. The development of anesthetics in the late nineteenth century made the gruesome pain of amputations a thing of the past, and the invention of the antiseptic surgery cleaned up the squalor of the nineteenth-century hospital.”

What changed? The short answer is the industrial revolution. A series of what Gordon calls “Great Inventions,” like the railroad, the steamship, and the telegraph set off this transformation. Electricity and the internal combustion engine continued it. And though these “Great Inventions” were perhaps most central, countless other technologies made life better in this period. The mason jar helped store food at home; refrigeration transformed food production and consumption; the radio changed the way people received information.

Gordon’s book The Rise and Fall of American Growth, from which I’m quoting, is rich with detail and data and well worth a read. Its conclusion, and my point here, is that the rapid rise in living standards over the past two hundred years is directly linked to new technologies. Technology isn’t the only thing that has driven progress, of course. More inclusive political institutions have obviously driven tremendous progress, too. But technology is a central part of progress, and without it our potential to improve human welfare would be more limited.

The theory

Technology has long played a central role in economic theory. How much an economy can produce depends in part on the availability of inputs like workers, raw materials, or buildings. But what determines how effectively these inputs can be combined — how much the workers can produce given a certain amount of resources and equipment? The answer is technology, and for a long time economists thought of it as outside the bounds of their models. Technology was this extra “exogenous” thing. It was “manna from heaven” — critical to explaining economic growth but not itself explained by economic models. As economic historian Joel Mokyr wrote in 1990, “All work on economic growth recognizes the existence of a ‘residual,’ a part of economic growth that cannot be explained by more capital or more labor… Technological change seems a natural candidate to explain this residual and has sometimes been equated with it forthwith.”

But around the time he was writing that, economists’ theory of technology was starting to change. Paul Romer, among others, started publishing models of economic growth that more directly accounted for technology. In these models, “ideas” were the source of economic growth, and the growth of ideas depended in part on how many people went into the “ideas producing” sector, sometimes called R&D. In 2018, Romer won the Nobel Prize in economics for this work. David Warsh’s book Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations is a wonderful read on this shift in growth theory.

My point here is simply to note that economic theory suggests that for sustained economic growth to happen, we need a steady stream of new ideas and new technologies. A theory is not evidence per se, but it fits with the point of this essay: if we want to improve living standards over time, technology will likely be important.

The evidence

If both the broad historical picture and economic theory support the idea that technology is essential for rising living standards, what about more micro-evidence? One wonderful study of this, written about by my former colleague Tim Sullivan, measured subscriptions to Diderot’s Encyclopedie, to measure how the spread of technical knowledge effected economic growth in Enlightenment-era Europe:

“Subscriber density to the Encyclopedie is an important predictor of city growth after the onset of industrialization in any given city in mid-18th century France.” That is, if you had a lot of smarty pants interested in the mechanical arts in your city in the late 18th century (as revealed by their propensity to subscribe to the Encyclopedie), you were much more likely to grow faster later on. Those early adopters of technology – let’s call them entrepreneurs, or maybe even founders – helped drive overall economic vitality. Other measures like literacy rates, by contrast, did not predict future growth. Why? The authors hypothesize that these early adopters used their newly acquired knowledge to build technologically based businesses that drove regional prosperity.

Another study of U.S. inventors from 1880 to 1940 links patenting to GDP at the state level. Yet another links a city’s innovation-oriented startups to its future economic growth. Another paper confirms that the rapid economic growth in the 1990s was due to technical change. This one links venture capital funding to economic growth. I could go on.

Policy, institutions, and culture

People often say that technology is a tool, and so neither inherently good or bad. That’s true enough, but what I’m arguing is that it’s an essential part of progress. If we want to improve human welfare, using technology well is going to be a big part of that at least in the long run.

Whether technology improves human welfare depends on a lot of things, including policy, institutions, and culture. Economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson write:

Economic institutions matter for economic growth because they shape the incentives of key economic actors in society, in particular, they influence investments in physical and human capital and technology, and the organization of production. Although cultural and geographical factors may also matter for economic performance, differences in economic institutions are the major source of cross-country differences in economic growth and prosperity.

In terms of policy, Gordon does a good job explaining how regulations around food quality helped improve welfare, limiting one of the major downsides to the mass production of food. Likewise, regulation was essential to the spread of the electric light, again to limit its downsides in the form of accidents. Mokyr has written extensively on the role of culture in promoting innovation and growth.

Being good at technology — being a society that harnesses it well — depends on much more than technical progress. But that’s part of what I’m arguing for when I lay out the optimistic case for technology. My hope is not just that we’ll blindly embrace new tech, but that we’ll build reliable, trustworthy institutions, create a culture that embraces innovation but acknowledges its risks, and regulate technology wisely with an eye towards both its benefits and its costs.

The electric light

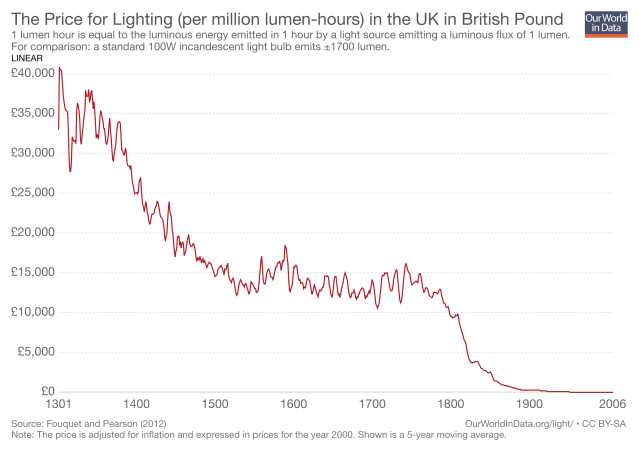

Light used to be fabulously expensive.

Over time, though, technology changed that. Humans gained control over their environment, opening up new possibilities in terms of how we work, how we entertain ourselves, the communities we live in, and more. I’ve written a lot about the electric light, based in large part on the book Age of Edison. And I see in that story the big points I’ve laid out here. The chart above gives the macro-historical story of light. It used to be wildly expensive, and now it’s something most people at least in developed countries can afford. It’s clear that it transformed societies for the better:

The benefits of electrical power seemed widely democratized. By the early twentieth century, all American town dwellers could enjoy some of the pleasure and convenience of an electrified nightlife and a brighter workplace, while domestic lighting was coming within reach of many middle-class consumers and a growing number of urban workers… In this respect, what distinguished the late nineteenth century technological revolution was not its creation of vast private wealth but the remarkable way its benefits extended to so many citizens. The modern industrial system built enormous factories for some but also served a more democratic purpose, improving ‘the average of human happiness’ by providing mundane comforts to the multitude. (Age of Edison 234-235)

But culture, institutions, and policy all mattered. Electric light caused accidents and required regulation. It created new opportunities for capitalists to exploit workers. It contributed to a growing urban-rural divide. The answer, I think, quite clearly is not to denounce the electric light or to roll the clock back to gas lighting. Rather it’s to acknowledge that maximizing the electric light’s benefits required more than technical change. America and the world were better off for that invention, but making the most of it required new rules and norms.

The future

Robert Gordon is skeptical about information technology, in terms of its potential to replicate the benefits of the industrial revolution. And in recent years key areas of the internet have not turned out well; I’m thinking of social media. Why be optimistic? Partly, I simply don’t see an alternative. I’ve argued that technology is one of the major forces for human progress and so without it the scope for improvements to human welfare is significantly diminished. But partly I’m optimistic because regulation, culture, and institutions can help make IT and the internet better. They can help us maximize the benefits we receive from them (which are already substantial). I have some thoughts as to what that might look like but the history of technology suggests that to get the most from any new invention requires participation from all of society. We need inventors, surely, and entrepreneurs. But we need critics, too, as well as politicians and regulators and activists. We need people to recognize the potential and the risks simultaneously, rather than focusing only on one or the other. What we need to make the most of technology is a well-functioning democracy.

Update: A literature review on technological innovation and economic growth.